Autumn has arrived. And that means it’s time to take down a volume of Sergei Yesenin and immerse ourselves in his autumn poetry. fall pieces.

The poetry of Sergei Yesenin is known worldwide. He wrote about nature and love, about life and inner struggles. Some of his works were playful and even mischievous. His poems have forever become part of world literature — and of our hearts.

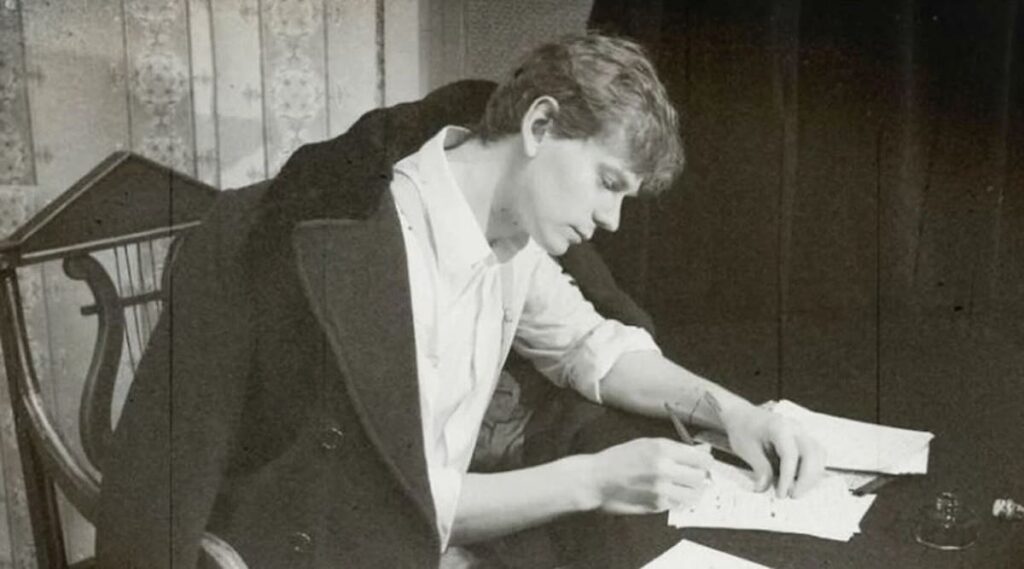

The Life of Sergei Yesenin

Sergei Alexandrovich Yesenin was born on October 3, 1895, in Ryazan Province. His passion for poetry began in childhood. Inspired by rural life, he wrote his first poem at just 9 years old. Nature and the simplicity of country living would run through his entire body of work.

Writer D. N. Semenovsky once said: “Organically, by blood, Yesenin was bound to the world he came from — to the fields and the village. And even while living in the city and absorbing its culture, Yesenin remained a singer of his native land.”

His parents imagined a teaching career for Sergei. But he went another way. He did not enroll at university and instead took a job at the publishing house Kultura. For a long time, he sent his poems to different publishers — but no one agreed to print them.

He lived in poverty and without recognition. Hungry for knowledge, Yesenin began attending evening lectures in history and philosophy, while taking on different day jobs to survive.

In 1913, the young poet became fascinated by the ideas of the Social Democratic Party. He printed political leaflets and spoke to workers. He took part in strikes and protests — experiences that left a mark on his writing.

Soon, Moscow publishers noticed him and began printing his poems. By 1916, Yesenin released his first poetry collection, Radunitsa. He refused to write odes to the Tsar — for which he was sent to a disciplinary battalion. But he never made it to the front, as the February Revolution began.

Fame had already found him, but life started to feel empty and careless. To escape this boredom, Yesenin began working on the poem Pugachev and traveled through the regions where Pugachev’s uprising had taken place.

In 1922, Sergei Alexandrovich traveled abroad — to Germany, France, Italy, and America. During this journey, he kept writing and even sketched the first draft of The Black Man.

Historians and contemporaries later called this poem the darkest in his career, even a premonition of his death. The next two years were fruitful: Yesenin published several books and wrote more than ten works. But by mid-1925, his mental and physical health collapsed. He was admitted to a psychiatric clinic.

Leaving treatment unfinished, he decided to start over and moved to Leningrad. On December 28, 1925, Yesenin was found hanged. Officially, it was ruled suicide — though theories remain that he did not die by choice.

Yesenin’s Personal Life

The poet was always popular among women. He loved noisy gatherings, always surrounded by admirers. But he also had serious romances.

In 1913, Sergei met Anna Izryadnova. They quickly began living together, but within two years separated, disillusioned with family life. They did, however, have a son together.

In 1917, Yesenin married for the first time. His wife was Zinaida Reich, secretary of the newspaper The People’s Cause. But their marriage also ended after just one year.

The greatest love of Yesenin’s life was the American dancer Isadora Duncan. They met in 1921 during her tour of Russia. A year later, they married. But in 1923, after traveling to America together, they divorced.

They were simply too different. They barely understood each other’s languages, their lifestyles clashed completely, and Isadora was 17 years older than Sergei.

In 1925, Yesenin married again, this time to Sophia, granddaughter of Leo Tolstoy. But this marriage also ended after just six months.

Sergei Yesenin lived a bright, though short, life. He left us a rich legacy of poetry that still feels relevant today. More than anyone, he captured the beauty of Russian nature.

Yesenin’s verses inspire pride in Russia. And to this day, his words echo in songs, films, and our collective memory.